Welcome to the 69th edition of #theFutureReadyAdvisor Newsletter!

Subscribe & join the conversation. Share comments and feedback.

“The same qualities that create extraordinary success can become the very barriers to sustaining it.”

In 2011, Ron Johnson was hired as CEO of JCPenney with the kind of fanfare usually reserved for superstar athletes. The man who had revolutionized retail at Apple and made Target “hip” was going to save one of America’s most dowdy department store chains. On the day his appointment was announced, JCPenney’s stock jumped 17%. Wall Street believed they had found their retail messiah.

Johnson had every reason for confidence. At Apple, he had created stores that generated $4,000 per square foot in sales—nearly double that of luxury retailers like Tiffany & Co. His Apple stores were temples of technology that turned shopping into an experience. At Target, he had transformed a discount retailer into a destination for stylish, affordable design. His track record was flawless.

Then came JCPenney, and everything unraveled.

Johnson applied the same methods that had made him a retail legend: eliminate coupons and sales in favor of “everyday low prices”, create boutique stores-within-stores, focus on experience over transactions. He refused to test these changes, famously telling his team, “We didn’t test at Apple.” After all, why test when you’ve already proven the formula works?

Seventeen months later, Johnson was fired. JCPenney’s sales had collapsed by $4 billion, same-store sales dropped 32% in a single quarter, and the stock price fell to levels lower than when he was hired. What had been hailed as one of retail’s most promising transformations became one of the most spectacular failures in business history.

Johnson’s story reveals a profound psychological trap: success doesn’t just build confidence—it creates an illusion of control that can blind us to when our proven methods no longer apply.

The Attribution Error Trap

What happened to Johnson wasn’t simply overconfidence—it was a fundamental misunderstanding of what had driven his success. At Apple, he was selling revolutionary products to early adopters who embraced change. The stores weren’t just retail spaces; they were showcases for lifestyle transformation. At Target, he was bringing design to mass market consumers hungry for affordable style.

But JCPenney’s customers weren’t seeking transformation or affordable style —they were seeking deals. Johnson attributed his Apple success to brilliant store design and customer experience, when much of it came from factors beyond his control: revolutionary products, a technology-hungry customer base, and a brand that represented innovation itself.

Similarly, consider the cautionary tale of “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap, who built a reputation as a corporate turnaround genius by slashing costs at companies like Scott Paper. When Sunbeam hired him in 1996, the stock price jumped 50% on the announcement alone. Wall Street believed his “slash and burn” approach was universally applicable.

Dunlap attributed his Scott Paper success to his aggressive cost-cutting methods. What he failed to recognize was that Scott Paper’s turnaround had more to do with a favorable market environment and the company’s underlying fundamentals than his management style. At Sunbeam, his methods led to accounting fraud and bankruptcy. The same approach that made him a hero at one company destroyed another.

Both Johnson and Dunlap fell victim to what psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error“—in this case, the tendency to attribute success to our own skills and methods while underestimating the role of context, timing, and factors beyond our control.

What We Control vs. What Controls Outcomes

The most dangerous aspect of the control illusion is how it prevents us from accurately assessing what we actually control versus what determines outcomes. Johnson controlled his retail strategies, store layouts, and pricing policies. But he couldn’t control JCPenney’s existing customer base, their shopping habits, or their emotional attachment to coupons and sales events.

At Apple, the context was everything: cutting-edge products, a tech-savvy customer base eager for the latest innovations, and a brand that represented the future. Johnson’s retail genius was real, but it was optimized for a specific environment. When he tried to transplant those exact methods to a completely different context, they failed spectacularly.

This pattern appears everywhere in business and investing. The real estate developer who built wealth during a boom struggles when credit tightens. The growth stock investor who dominated bull markets gets crushed in bear markets. The sales leader who excelled in one industry fails in another with different customer dynamics.

Research from Ellen Langer demonstrates that when people experience positive outcomes, they overestimate their influence on results. Success creates a feedback loop where confidence breeds more confidence, even when that confidence isn’t justified by the underlying factors driving success.

For wealthy individuals, this dynamic is particularly acute. Studies show that wealthy people score lower on agreeableness—they’re more likely to trust their own judgment over outside input. These traits often contribute to their success, but they also make them more susceptible to attribution errors when contexts change.

The Hidden Variables

The tragedy of both Johnson and Dunlap’s stories is that they focused on replicating their methods without understanding the hidden variables that had driven their success. Johnson didn’t just succeed because of store design; he succeeded because he was designing stores for customers who wanted what he was selling. Dunlap didn’t just succeed because of cost-cutting; he succeeded because he was cutting costs at companies that were genuinely bloated and operating in favorable market conditions.

When successful people move to new environments, they often try to recreate their previous conditions rather than adapting to new ones. The tech CEO who micromanages every decision because that worked at a startup struggles when their company reaches 1,000 employees. The investor who made fortunes buying distressed assets in the 1990s can’t understand why the same approach fails in a different credit environment.

I’ve seen this repeatedly in wealth management. Clients who built fortunes through concentrated stock positions resist diversification, even when their circumstances have completely changed. They attribute their success to superior stock-picking ability, when much of it came from being in the right sector at the right time with enough risk tolerance to hold concentrated positions.

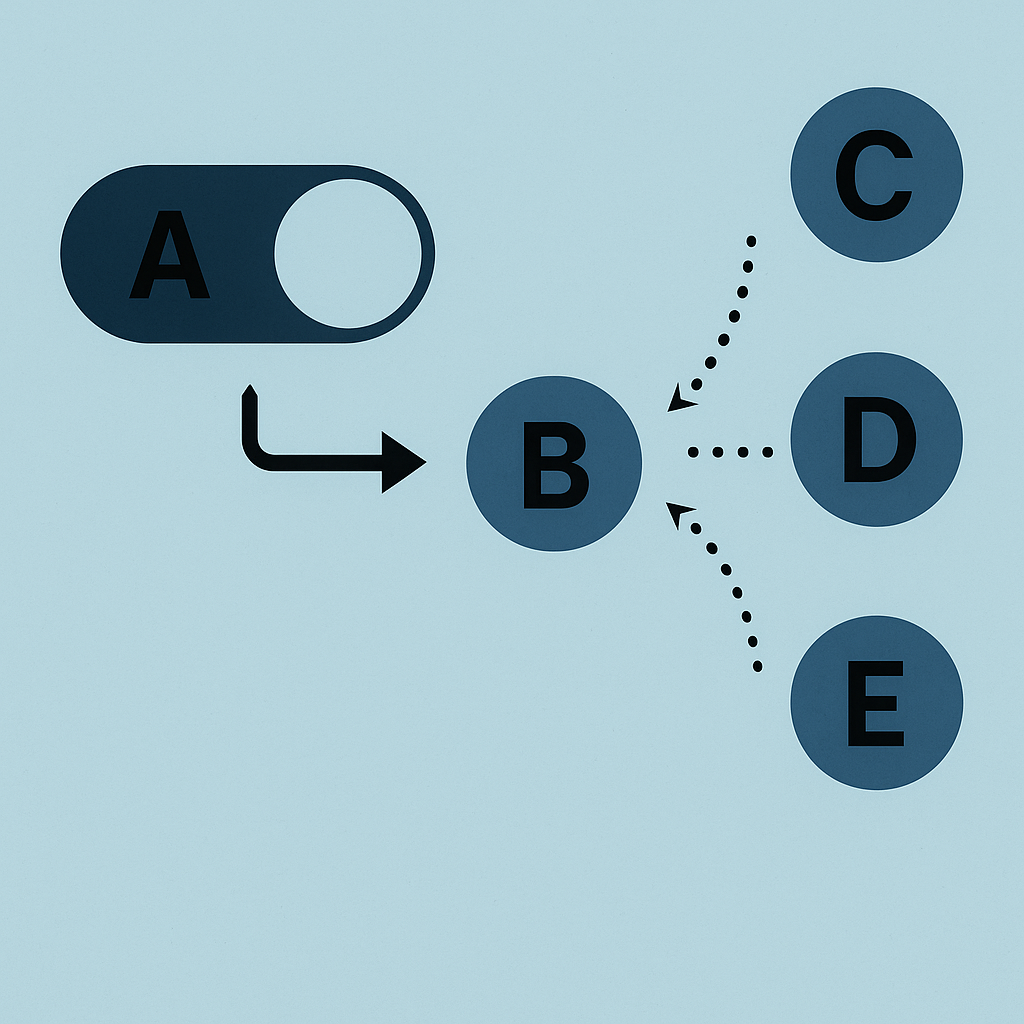

The control illusion makes us confuse correlation with causation. We assume that, because we did A and B happened, A caused B. But often, C, D, and E, factors we didn’t control or even notice, were the real drivers of B.

The Advisor’s Challenge

For financial advisors, understanding the control illusion is crucial because it explains why rational arguments often fail with successful clients. When you present data showing why they should diversify their concentrated stock position, you’re not just challenging their portfolio; you’re challenging their identity as someone who makes smart financial decisions.

The traditional advisory approach of education and persuasion often backfires with these clients. The more evidence you present that contradicts their approach, the more threatened they feel, and the more they resist. They didn’t build wealth by accepting others’ advice; they built it by trusting their own judgment.

This is why technical expertise alone isn’t sufficient for working with sophisticated clients. You need to understand the psychological dynamics that are at play. The most successful advisors I know don’t try to overcome their clients’ need for control; they find ways to respect it while gently expanding their perspective.

Modern Manifestations

The control illusion isn’t just a problem for individual investors; it shapes entire organizational cultures. Consider how many companies struggle with digital transformation because their leadership teams built their careers in pre-digital environments. Their past success creates confidence in approaches that may no longer be optimal.

We see this in the resistance to remote work policies. Leaders who built successful cultures through in-person management struggle to adapt to distributed teams, not because remote work doesn’t work, but because their identity is tied to their traditional leadership methods.

In politics, we see leaders doubling down on failing policies rather than admit error, because their political identity depends on being right. In healthcare, we see experienced practitioners resist evidence-based protocols that contradict their clinical experience.

The pattern is universal: success creates identity investment, which creates resistance to change, which can ultimately undermine the very success it was meant to protect.

The tragedy of the control illusion is that it prevents successful people from becoming even more successful. Johnson’s resistance to testing and adaptation didn’t just threaten JCPenney; it prevented him from learning approaches that could have made the transformation work. His past success became a prison, constraining his ability to evolve his methods.

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly: successful individuals whose greatest limitation isn’t lack of resources or opportunities, but their inability to distinguish between what they control and what they don’t. Their confidence in replicating past methods prevents them from adapting to new realities.

The irony is profound. The decisiveness and confidence that have driven extraordinary success can become the very barriers to sustaining it. The more successful someone becomes, the more they have to lose by admitting their approach might need adjustment based on new circumstances.

For advisors, this creates both a challenge and an opportunity. Those who learn to help clients separate their genuine skills from favorable conditions—who can guide them in adapting methods without threatening identity—become invaluable partners rather than mere service providers.

The lesson here isn’t that successful people are stubborn; it’s that they’re trying to maintain control in an uncertain world. And understanding what we can and cannot control is foundational to thriving when the future won’t cooperate. In fact, it’s the “C” in my CASE Foundation for navigating uncertainty: Control—focusing your energy on what you can influence while accepting what you cannot.

📥 Get the free guide: The Uncertainty Advantage—a decision-making framework for leaders navigating change.

Johnson eventually found success again with his startup Enjoy, but only after learning humility and the importance of context. The lesson wasn’t that his methods were wrong—they had worked brilliantly in the right environment. The lesson was that even the best methods need constant adaptation to new circumstances, and success can make that adaptation surprisingly difficult.