Welcome to the 73rd edition of #theFutureReadyAdvisor Newsletter!

Subscribe & join the conversation. Share comments and feedback.

When Boeing’s Engineers Knew—But Nobody Listened

In 2018, Curtis Ewbank, a senior engineer at Boeing, sent an urgent email to his managers. The 737 MAX’s new flight control system, MCAS, was behaving unpredictably in simulators. Pilots were struggling to understand it. Ewbank wasn’t flagging a known risk; he was signaling something more troubling: deep uncertainty about how the system would perform in real-world conditions with real pilots under real stress.

His warnings went unheeded. Boeing’s leadership had conducted risk assessments. They had probability models. They had calculated failure rates. Everything looked acceptable—on paper.

Five months later, Lion Air Flight 610 crashed into the Java Sea, killing all 189 people aboard. Four months after that, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crashed, killing 157 more. The 737 MAX was grounded worldwide for 20 months. Boeing faced over $20 billion in costs and criminal prosecution. More tragically, 346 people lost their lives.

The failure wasn’t a lack of data or analysis. Boeing had sophisticated risk management systems. What they lacked was the wisdom to distinguish between risk—which they could model and manage—and uncertainty—which defied their models entirely.

This distinction isn’t academic. It’s the difference between confidence and hubris, between preparation and blindness, between adaptation and catastrophe.

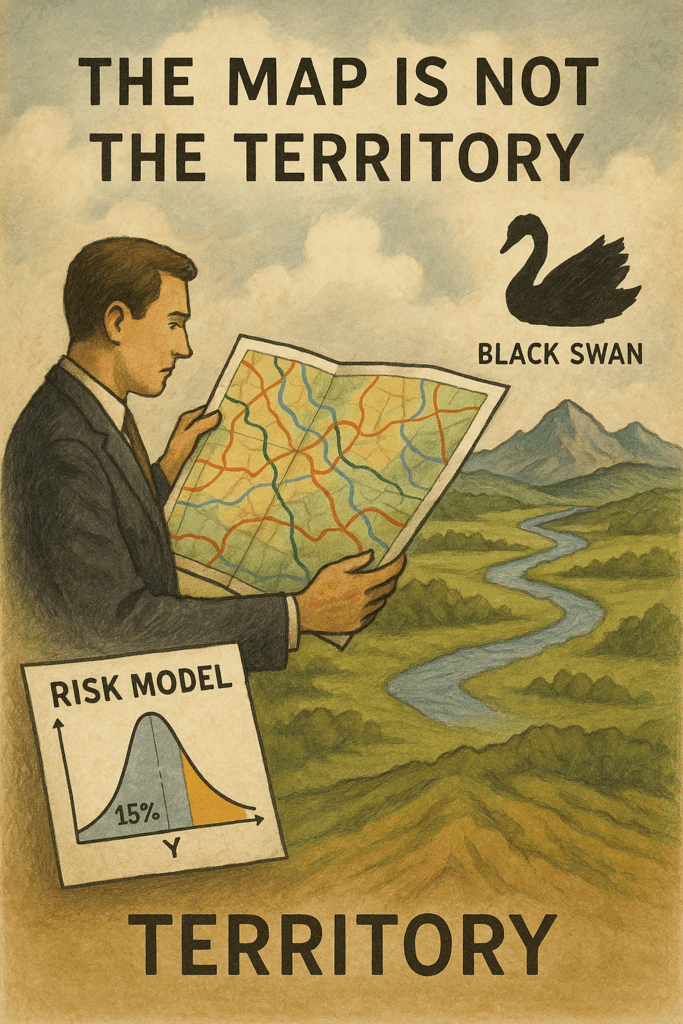

The Map Is Not the Territory

Most leaders are trained to manage risk. We learn probability theory, statistical analysis, and scenario planning. We build models that tell us: “There’s a 15% chance of X happening, and if it does, we’ll respond with Y.” This works very well in stable, predictable environments.

But as mathematician and philosopher Alfred Korzybski famously observed, “the map is not the territory.” Our risk models are maps; simplified representations of a far more complex reality. And like all maps, they work until they don’t.

Risk exists when you know the possible outcomes and can assign probabilities to each. When you diversify an investment portfolio, you’re managing risk. Historical data gives you reasonable probability distributions. You might lose money, but you can quantify how much and how likely.

Uncertainty exists when you don’t know the possible outcomes, let alone their probabilities. It’s the category of events Nassim Taleb called “Black Swans”—highly impactful, rare, and unpredictable in advance, yet obvious in hindsight.

According to research published in Strategic Management Journal, organizations that conflate risk and uncertainty consistently make two critical errors:

- Over-confidence in predictions: They believe their models capture more of reality than they actually do

- Under-investment in adaptability: They allocate resources to optimize for predicted scenarios rather than building capacity to respond to the unpredictable

Boeing made both mistakes. Their risk models said the MCAS system was safe enough. Their organizational design prioritized cost efficiency over adaptive capacity. When reality diverged from their models, they couldn’t adjust fast enough.

The October 2025 Everest storm revealed the same pattern. Trekking companies optimized for the risks they could calculate—altitude sickness, typical weather variations, equipment needs. They didn’t build in the adaptive capacity needed for the uncertainty of extreme, unprecedented conditions.

Why Smart Leaders Get This Wrong

The Boeing tragedy reveals a troubling pattern. It’s often the most sophisticated organizations that fall hardest into the risk-uncertainty trap. Why?

Success breeds confidence in your models. When your risk management approach works repeatedly, you begin to trust it implicitly. Boeing had decades of successful aircraft development. Their processes had worked for the 747, 767, 777. Why wouldn’t they work for the 737 MAX?

Similarly, October trekking on Everest had worked reliably for decades. Tour operators had years of data showing it was the optimal season. Until suddenly it wasn’t.

Pressure favors the quantifiable. Boards want numbers. Investors demand projections. Stakeholders expect certainty. When you can’t quantify something, it’s tempting to either ignore it or force it into a risk framework where it doesn’t belong.

Boeing was under intense pressure to compete with Airbus’s fuel-efficient A320neo. Acknowledging uncertainty about MCAS would have meant delays, added costs, and competitive disadvantage. So they forced it into their risk assessment framework and declared it manageable.

Organizational structures resist ambiguity. Most companies are designed to execute plans, not to navigate uncertainty. Clear hierarchies, defined processes, and measured KPIs all assume a relatively predictable environment. When Curtis Ewbank raised concerns about MCAS, they didn’t fit neatly into Boeing’s risk assessment framework; so they were minimized.

Research from Harvard Business School shows that cognitive biases, particularly anchoring bias and confirmation bias, intensify under pressure. Leaders anchor to their initial risk assessments and then seek information that confirms those assessments, even when evidence of uncertainty emerges.

The Advisory Practice Parallel

If you’re in financial services, this pattern should feel uncomfortably familiar. How many advisory practices treat market volatility as pure risk, something to be modeled and managed through diversification and rebalancing, while ignoring the fundamental uncertainty of market regime changes, regulatory shifts, and technological disruption?

Consider the advisory firms that were optimized for pre-2008 conditions: heavy in alternative investments, structured products, and leverage strategies. Their risk models looked solid. Then the financial crisis arrived; not as a predicted risk event, but as a cascade of uncertainties that their models couldn’t capture.

Or think about the practices perfectly positioned for face-to-face, relationship-driven advice in early 2020. Their business models had worked for decades. Then COVID-19 forced an overnight shift to virtual everything. The firms that survived and thrived weren’t those with the best risk management; they were those with the adaptive capacity to navigate profound uncertainty.

The same pattern plays out in corporate strategy, product development, and talent management. Leaders build elaborate risk management systems while ignoring the uncertainty that will actually determine their fate.

Four Practical Distinctions

To navigate uncertainty rather than just manage risk, leaders need practical frameworks for distinguishing between the two:

1. The Probability Test Can you assign meaningful probabilities to outcomes based on historical data or first principles? If yes, you’re likely dealing with risk. If no, if you’re just guessing at probabilities to make your spreadsheet work, you’re facing uncertainty.

The Everest hikers could calculate risk based on October weather patterns from the past 50 years. They couldn’t calculate the probability of an unprecedented storm because it fell outside historical patterns.

2. The Model Stability Test Would experts with the same data reach roughly the same conclusions? Risk lends itself to convergent analysis. Uncertainty produces divergent interpretations. When Boeing’s internal engineers disagreed fundamentally about MCAS safety, that was a signal of uncertainty, not risk.

3. The Surprise Test If the event occurred, would you be genuinely surprised, or would you think “I should have seen that coming”? True uncertainty surprises even in hindsight, while risk events feel predictable after the fact.

When experienced Everest guides say “I’ve never seen weather like this in October in my entire career,” that’s uncertainty. When a diversified portfolio loses 5% in a correction, that’s risk.

4. The Response Test Do you have a predefined response plan, or would you need to figure it out in real-time? Risk allows for scenario planning and predetermined responses. Uncertainty requires adaptive capacity and improvisational capability.

Three Actions for Leaders

1. Separate Your Risk Register from Your Uncertainty Radar Create two distinct tracking systems. Your risk register captures known risks with assigned probabilities and mitigation plans. Your uncertainty radar flags areas of deep ambiguity where you don’t know what you don’t know. Review the uncertainty radar quarterly, not to resolve the uncertainty, but to ensure you’re building adaptive capacity in those areas.

2. Create Safe Spaces for Dissent The Curtis Ewbanks in your organization need permission to raise uncertainty without being labeled alarmist or negative. Institute regular “red team” exercises where the explicit goal is to identify what your models might be missing, not to optimize the models themselves.

When someone says “I’ve never seen conditions like this before,” that’s not pessimism; that’s a signal you’ve left the domain of risk and entered uncertainty. Listen to those signals.

3. Invest in Response Capacity, Not Just Prediction Accuracy Shift 20% of your strategic planning resources from trying to predict the future more accurately to building your organization’s capacity to respond to unpredictable futures. This might mean cross-training staff, building financial buffers, or maintaining strategic optionality.

The hikers who survived the October storm weren’t those who predicted it; they were those who could adapt when it arrived.

The Wisdom to Know the Difference

There’s a serenity prayer in recovery communities: “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Leadership requires a similar wisdom: knowing when you’re facing calculable risk versus irreducible uncertainty, and adjusting your approach accordingly.

Boeing’s tragedy wasn’t caused by taking risks; it was caused by treating uncertainty as if it were a risk. They built sophisticated models when they needed to build adaptive capacity. They optimized for efficiency when they needed to preserve flexibility.

The Everest storm wasn’t a failure of risk management; the hikers had managed known risks perfectly. It was a reminder that some conditions can’t be predicted, only navigated in real-time.

Understanding the difference between risk and uncertainty—and developing the tools to navigate both—is central to my upcoming book, The Uncertainty E.D.G.E.: Lead with Clarity, Adapt with Confidence, Win with Conviction. The book provides practical frameworks for leaders who need to act decisively, even when the future won’t cooperate. It’s available for pre-order now [PRE-ORDER LINK].

One early reviewer of the book said:

Sam has written the kind of book every entrepreneur and leader needs right now — clear, engaging, and deeply practical. In a world where uncertainty is the only constant, The Uncertainty Edge transforms it from a threat into a competitive advantage. Through real-world stories and actionable tools, Sam shows how to lead with clarity amid chaos. The E.D.G.E. Framework is both memorable and immediately applicable — a must-have toolkit for anyone building, scaling, or leading through change. Saar Pikar | Managing Director, Head of Ventures and Growth | Private Capital | OMERS

Your organization will face both risk and uncertainty. The question is: can you tell the difference? And are you building the capacity to handle both?

I’m Curious:

Think about a major strategic decision your organization made in the past year. Were you managing known risks, or were you actually navigating deep uncertainty while pretending it was risk? What would you do differently now? Share your thoughts in the comments.

— Lao Tzu (Ancient Chinese philosopher)